Alchemy Film & Arts

Using film as a way to come together, have conversations and strengthen community.

SHORTS: STILL PROCESSING

FRIDAY 1 MAY

17:00 – 18:00 BST

Watch the programme HERE. All programmes begin at their advertised time.

This programme contains flashing / strobe effects

PROGRAMME NOTES

by Kerry Jones

The process of processing is physical, emotional, mechanical, chemical – an action to start, end, change, preserve, layer and morph. The eight films in this programme remind us all we are still processing.

In Yoni Bentovim’s Snow, nothing is ever still. Text from a book is photocopied, wall-projected then filmed on 16mm. The physicality of the formats focuses our attention, searching for movement. In Photograph Jessie Growden takes her personal photograph collection and methodically destroys it by shredding, deselecting through a systematic process, accompanied by heartfelt singing.

In Postdigital Flipbook, Pablo-Martín Córdoba presents an algorithmic selection of celebrity faces at speed, flipbook style. No singing here, but an intense sound of a slide carousel moving to the morphing animated images. Avant Kinema’s Flow State is inspired by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s theories of flow, and takes full enjoyment in the process of scratching, animating and hand-processing Super8 film partnered with an improvised soundtrack of guitars and percussion. In this immersive trip, process is key.

16mm filmstock is the starting point for A Venture into Vegan Filmmaking, for which Josephine Ahnelt and Esther Urlus set out to prove that vegan film emulsions are possible, replacing gelatine with PVA. The result is a visceral, textural image from the past and the future. In Karel Doing’s new work Phytography, leaves, petals and stems imprint their own images on the film stock, producing swirling shapes, patterns and organic rhythms: a process that is also the result.

Derek Jenkins positions the dandelion as conspirator, metaphor and film processor in The Shouting Flower, a work about collaboration and process documenting its own creation. In Searching for Beauty in Student Loan Debt or at Least the Envelopes in Which it Comes, Nicky Tavares reminds us of the process of making within a society based on profit and capitalised interest. Screen printing the insides of debt-letter envelopes onto 16mm film, Tavares invites us to ‘dream in colour of solvency that may never come.’

SNOW

Yoni Bentovim – 2’00 – UK

World Premiere

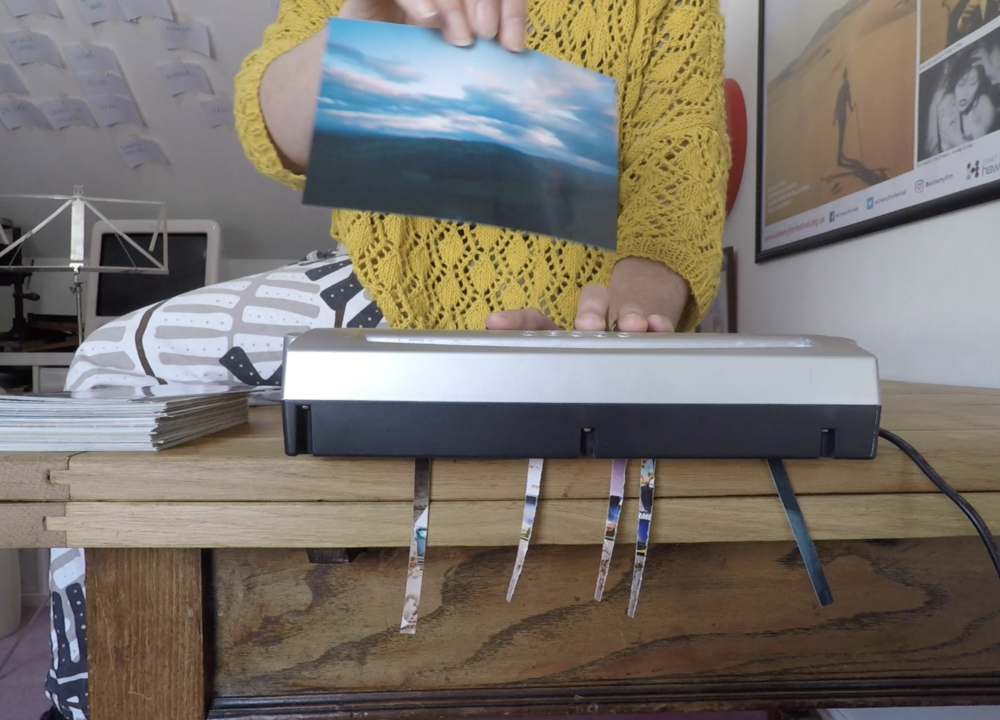

PHOTOGRAPH

Jessie Growden – 7’40 – UK

World Premiere

POSTDIGITAL FLIPBOOK

Pablo-Martín Córdoba – 4’30 – France

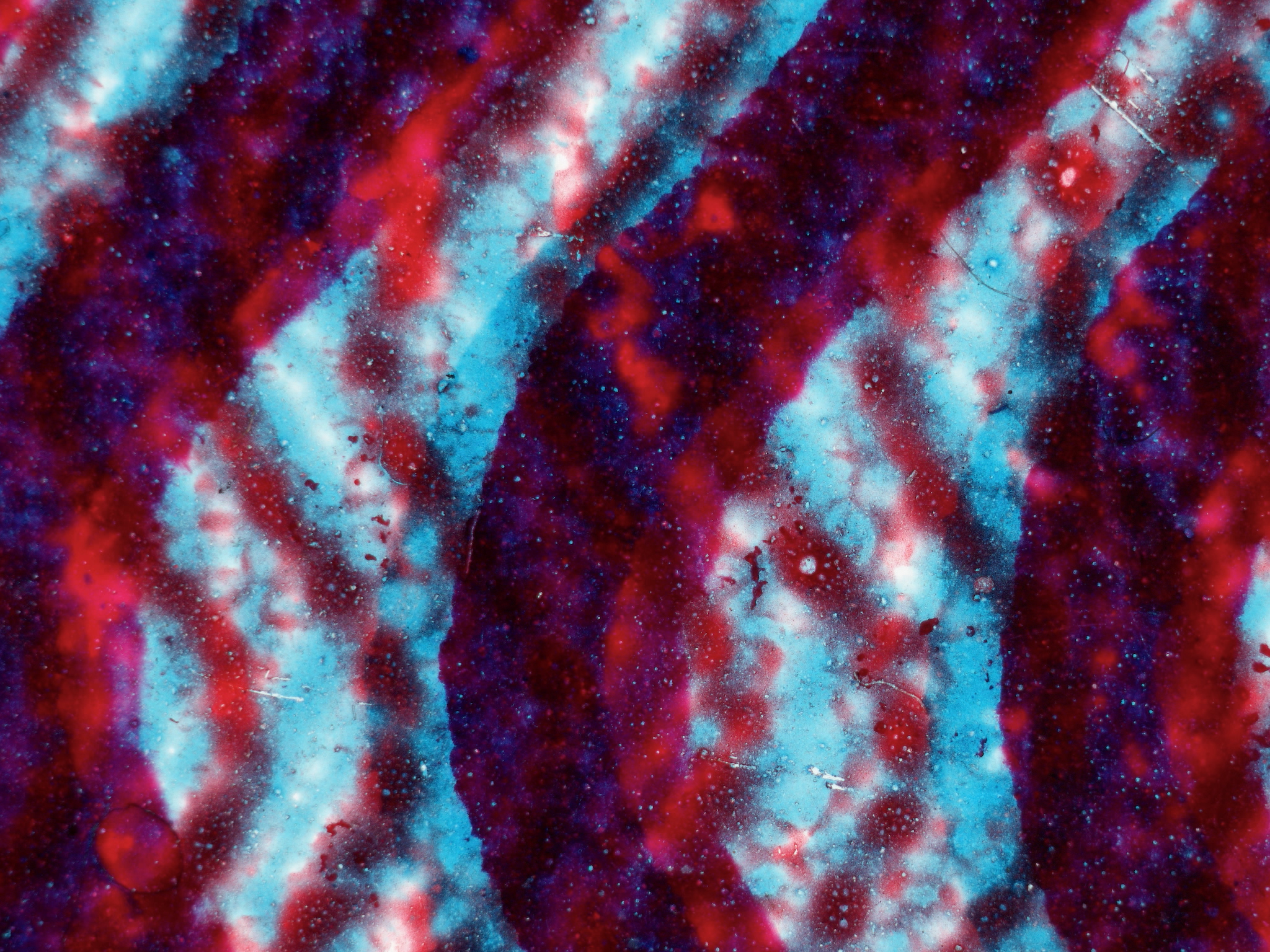

FLOW STATE

Avant Kinema – 8’54 – UK

World Premiere

A VENTURE INTO VEGAN FILMMAKING

Josephine Ahnelt – 2’52 – Austria

World Premiere

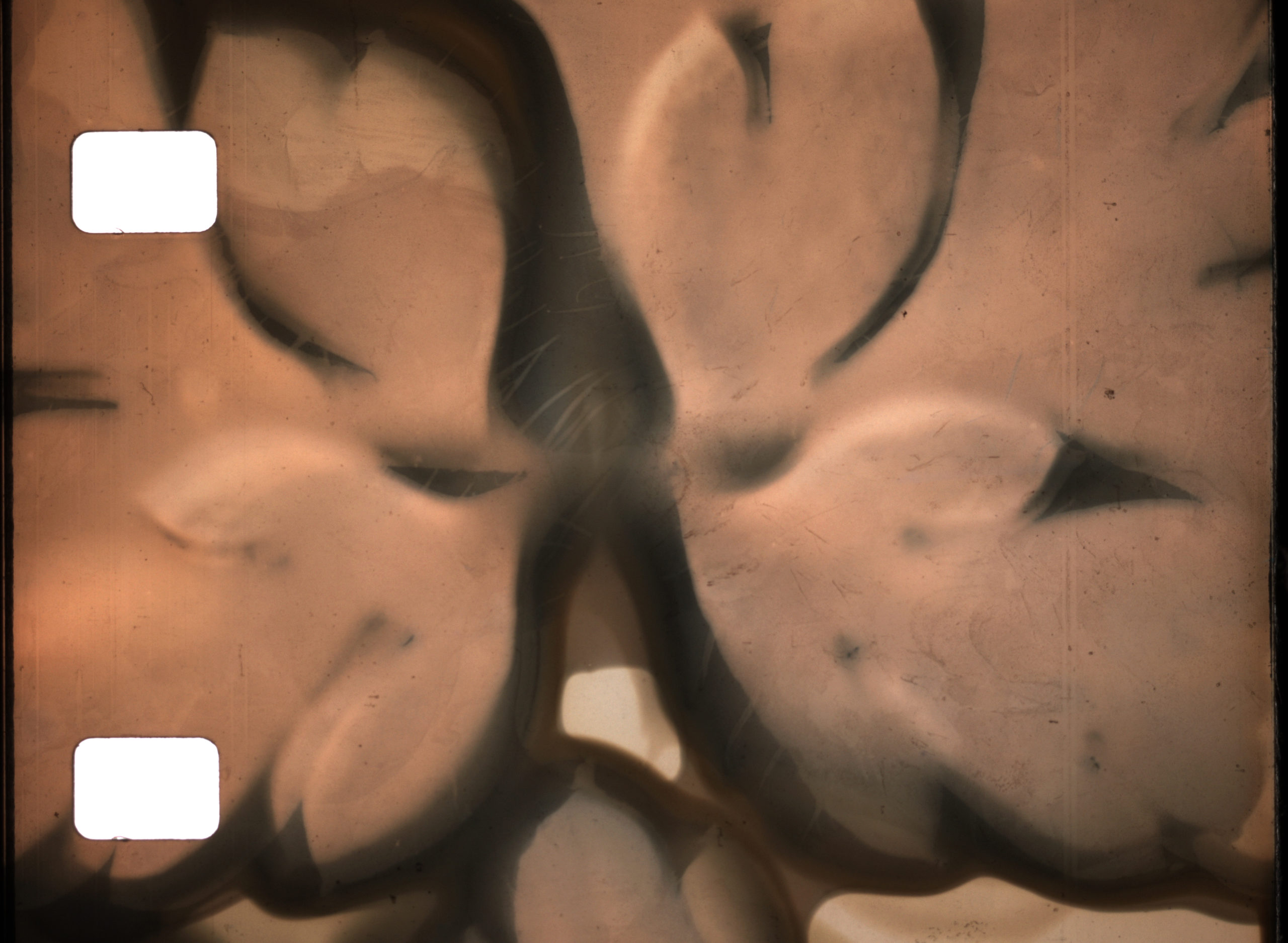

PHYTOGRAPHY

Karel Doing – 8’05 – UK

World Premiere

THE SHOUTING FLOWER

Derek Jenkins – 12’02 – Canada

European Premiere

SEARCHING FOR BEAUTY IN STUDENT LOAN DEBT OR AT LEAST THE ENVELOPES IN WHICH IT COMES

Nicky Tavares – 5’00 – USA

International Premiere

ARTIST Q&As

Alchemy asks…

Yoni Bentovim, Snow

There is stillness in your film, and yet it is a moving image. Tell us about the process in making it, and about your approach to stillness and movement.

Stillness is merely a human concept. I find this notion interesting and wanted to explore it. The basic idea of this minimal exercise is that as we read the still text it directs us to our own act of reading in a self-referential way. When we are done reading, the text stays there and we start to look at it as a still object, echoing in our mind the content we just read. Our attention span becomes focused in our own thoughts, and we can feel how they never rest for a second – never still.

Technically what I did was take a still photo of the page with the paragraph from Creative Evolution by Henri Bergson. I then projected the photo on a wall and filmed the projection with a 16mm camera. Unlike digital, the grain of film is not uniform and therefore never the same and this contributes to the feeling of flow and movement.

The passage of text ends with the word ‘snow’, drawing parallels between the swell of memory over duration and the mass of a snowball on snow. But your film is about another ‘Snow’ also, in tribute…

That’s correct! The word ‘Snow’ also refers to the filmmaker Michael Snow. I love his work and this short film is my small tribute to him. My interest in dealing with text in film started after seeing Snow’s 1982 film So is This.

Jessie Growden, Photograph

Your film is a sequence of still photographs being shredded. It documents a way in which images can be destroyed, but it’s also a document of new images being made.

I’d used the KonMari method to sort through all of my physical photos. The method involves holding and considering each object you own and establishing whether they ‘spark joy’. Everything that doesn’t spark joy is discarded. So the photos in Photograph are the ones I decided not to keep, and although this means they didn’t spark joy for me – they’re all either underexposed, overexposed, embarrassing, or just one of a series of photos that are of the same thing.

I should have just recycled them or something, but this stack of pictures was just too close to me to throw away, even if they didn’t make me feel warm and fuzzy inside when I picked them up. I had to do something to memorialise these unwanted, embarrassing old images, without spending hours scanning them – they weren’t quite worth that. Weirdly, sharing them as a film now they are gone is making me feel more sentimental about them, and I’m appreciating them as a video that sparks joy for me, and feeling kind of released that these terrible photos are going to be seen by many more people than the photos I decided to keep. It feels safer, too – the image has been sped up, and they’re almost always in motion, which lessens that universal teenage sting, ‘What on earth was I thinking?’ when certain images pass through the shredder.

Yes, I have been brainwashed by Marie Kondo. The Life Changing Magic of Tidying is actually magic.

This is another one of your ‘structural’ films which we love so much, where the duration is determined by the completion of a single task. In this case, there’s also a soundtrack which governs the length of the film…

Amazingly, there are very few songs that are actually called Photograph. There are just a lot that you’d think were called photograph. I wanted to make a soundtrack that was sticky and sentimental, to react to the ruthless shredding of photographs, and would mess around with the rhythm made by the scanning. I love what a good rhythm can do to your head in a structural film, the trance they can send you into. I compressed the image to fit the length of the songs for mostly practical reasons of making it all fit together neatly. I think it’s important to stick to these arbitrary made-up rules. It’s satisfying.

Should I say something about the ukulele? It’s bubble-gum pink, I bought it for £12.99 in Oxfam in Hawick, and I really do want to learn how to play the thing properly. In the current state of lockdown, I’m not sure whether it’s better to practice in the house, upsetting my partner, or to practice in the backyard, upsetting the neighbours. I’ve reached the stage of womanhood where I find using a bright pink musical instrument empowering, which is nice, and it will one day be seen on video. Teenage dreams of becoming a rock star may yet happen…

Pablo-Martín Córdoba, Postdigital Flipbook

Just how many images are we seeing here, and how are we seeing them?

A massive amount work is done by, so to speak, a bunch of craft-worked algorithms specially created for the project. These algorithms surf the internet indexing images showing human faces. For this, I think we can say that it is a form of exploitation of the big data. At the time the film was made, the algorithms had identified and processed 200,000 images. The set of images which make this film is the result of a ‘path’, one among the many, many possible paths within this multi-layered space made out of pictures showing faces. This path covers about 10,000 images. I am currently working on a web version of the project, interactive and still unpublished, associated with a database containing more than 2 million images.

Our brains are processing a rapid succession of stills, but do we ever see the same still twice? What kind of rules did you set yourself in making this film?

Yes, you may see the same still twice if you ‘pass’ through the same ‘place’ twice, and in the film it happens. About rules, I tried to keep a limpid protocol all along: facial features are just pointed by artificial intelligence, and then all the images are ordered by proximity of the pointed facial features. Each image is associated with six other neighbouring images to the right, to the left, top, bottom, front, back. A ‘space’ is thus created. Then comes the temporality of the film, that was also automated and calibrated until I got something that I liked. There is mainly a slow rhythm, a fast rhythm, and the transitions among them. The slow rhythm allows the viewer to remain on each individual image, to capture some interesting and funny sequences, to see that for some images the faces are part of paintings, tattoos, t-shirts, album covers, etc. But most of all, the slow rhythm allows us to understand the mechanism put in place when the acceleration begins.

The final acceleration seems to me to express a fiction, as if the 4 minutes and 40 seconds of the video actually correspond to a system that slows down to give itself to be seen, but that the natural state of this system is accelerated, it is a non-human speed. In any case the acceleration seems to me to suggest all the possibilities that the 4-minute, 40-second video cannot show. During accelerations, the meta-face usually manifests. It is a face that is not contained in the individual images, but which is attributed to the moving image by our visual perception system. Another fiction arises – may we say that the moving face in the film is the face of the big data?

Avant Kinema, Flow State

What is the ‘flow state’, and how did you come to deploy or enter it in making this work?

Roger Simian: Theories on the flow state were put forward in the mid-1970s by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, a Hungarian-American psychologist, and it is associated with positive psychology: the study of wellbeing in individuals and society, focusing on those positive areas of our experience which make life worthwhile – the good life. The flow state is a state of mind that we can all enter whenever we spend a long period of time engaged in an activity – especially an activity that’s creative. Being in the flow state is an enjoyable, almost hypnotic sensation and, when your mind is lost in that realm, you zone out, lose track of time, become unaware of anything else going on in the environment around you.

It seems to us that there must be some evolutionary purpose for the flow state. It’s probably allowed the primitive consciousness of early humans to expand, through all those ‘Eureka!’ moments and innovations which have driven our civilisations and societies forward. By entering this state, humankind has been able, at times, to focus all attention on one issue or topic at a time, draw on the full strength of our creative thought and crack problems that have seemed unfathomable. The flow state was probably involved in creating most of the great works of art, music, literature, architecture etcetera throughout history.

It may well be the equivalent to the tripped-out, hypnotic state people have been able to access through meditation or shamanic dancing, drumming, chanting and singing. Obviously mind-altering substances, from alcohol to drugs, could produce artificial effects, which have a similar feel.

Our son, Nico, is autistic and we can see his complete concentration on one action or sound or image or experience for lengthy periods of time as very similar to the flow state. When he is ‘stimming’ – self-stimulating by repeating an action or movement or sound over and over and over – he is so engrossed that it can take quite a bit of effort to break through the bubble and get his attention. We’ve realised that we, as his parents, look a lot like that when we’re engaged in creative activities and have entered the flow state.

Whenever Sarahjane handcrafts an analogue film, by painstakingly scratching, colouring and manipulating the film itself – as she did with this current movie – it is such a time-consuming and enjoyable activity that she becomes engrossed, unreachable, loses track of time.

The way we composed and recorded the soundtrack for the film had a similar effect on us. The music was mostly improvised on top of a set, rhythmic backing track. We both recorded various guitar parts and used experimental techniques for drawing strange, musical sounds from the instruments, by detuning or retuning the strings and using objects like drumsticks as guitar slides or jamming these between the strings. Because we were not directly following traditional melodic scales, or the strictly marked out spacings of the fretboard – the equivalent of a piano’s keys – we were able to become even more immersed in a kind of hypnotic mode of sound-making.

What kinds of structures, if any, do you put in place with a film like this? It unfolds as if it’s come into being of its own accord, but to what extent is it authored?

Sarahjane Swan: Don’t quote us on this but, as far as we can work out, one second’s worth of Super8 film – 18 frames – is around three inches long. With this in mind, I can have an idea of what 18 frames of scratch footage looks like as I’m working on a piece of film. I don’t measure anything out, and I use Super8 film that has no obvious frames, so I have no real visual guidance, just a memory in my mind of what 18 frames looks like, roughly. This means I can scratch and colour and draw without a definitive rule.

I want to get lost in the mark-making and make fleeting decisions about the length of line or if I repeat a pattern or scratch or shape. This abandon gives these symbols free movement. I can either repeat or keep creating new scratches one after the other, giving a flowing sensation to the process. I love colour and, again, it’s really all chosen because it feels right in that moment. There is not a lot of taking time and deliberating. It’s much more of a moving, flowing process.

I might make a very long scratch across a lot of the film at once or I may just make short, sharp cuts or score circles over and over, or just use the colour and create a shape with that. I truly do get lost in time, in space. After doing this to 50 feet of film it’s amazing to then feel the flow in a completely different way once you play back three minutes and twenty seconds worth of footage at 18 frames per second, with those tiny 8mm frames blown up to fill a computer or projector screen.

I get lost all over again watching the scratches I’ve made dance, free of any restriction. It comes alive in the watching. Somehow a magic happens and sometimes the scratches can look like they are running up the way visually and then change direction and flow downwards. I don’t know why this happens. I think our creative minds want to see these changes and our eyes and minds make that magic happen. To scratch 50 feet of Super8 film is a real labour of love. It’s very intricate and I use an eye piece and a light box to see where I am scratching. I love to get lost in the process and I find it very relaxing and satisfying. Watching the film back I find magic and freedom.

In post-production, we make a digital scan of the handcrafted film so that we can work on it some more in the computer, if we want to, and make a file that we can upload or share with festivals. With Flow State, we made no actual changes to the colour – they are that vivid. We did slow the film down from 18 frames per second to ensure that it all flows at a nice pace, not so fast that the details are lost, becoming invisible to the eye. Sometimes if these images hit you at too great a speed it hurts your head and, although the music here does have an intense, almost disturbing edge to it, that’s not the effect we were after at all with the imagery.

Again, the speed we opt to run the clip at is a very instinctive decision, as with most aesthetic and artistic choices. This is not about rigid mathematics. It’s about how something looks, sounds or feels in the instant. If we were trying to be purist, we would insist on playing the clip at 18 frames per second, or perhaps the cinematic industry standard of 24 frames per second, or some kind of mathematical division of those. If we used a traditional projector to bring this film to life, we would be restricted to the frame rates that the machinery made available. Editing on the computer gives us the freedom to play a clip at 32 or 47 frames per second if that’s what looks best to us. Anything that gives you more freedom is a good thing.

This process changes with every scratch film. No two are the same. This way of working has many beautiful aspects and one of them is that when you blow up the individual frames of the 50-foot film, each single frame looks like a painting in itself. Yes, this could be seen as a very long, laborious way of working but how long would it take you to paint 3600 paintings? That’s how many frames there are in a cartridge of Super8. What you have created at a miniscule size changes when it is blown up in size. You can see every fibre of the colour marks, and every fine, exquisite movement of a scratch. That’s very beautiful to us.

Karel Doing, Phytography

Phytography is, ostensibly, all about process – using the internal chemistry of plants to make an image and develop film. To what extent is the final result here less important than the way it is made?

The short answer would be: the process is the result. I am definitely very fascinated by this technique: using plants to generate images directly on photographic emulsion. It is great to work outside with very few tools and only a minimum of materials. Making films in photochemical images in full daylight is amazing: it has allowed me to take my practice out of the darkroom into sunshine.

However, the film is still a precise selection of a much bigger collection of footage. I approach my results as if I am translating from a foreign language. There is no dictionary and no online course, everything has to be deciphered from scratch. The final result is an attempt to make sense of the perceived signals. This process of translation is extended to the audience. Their ‘task’ is to take the process of translation a step further.

At last year’s festival we showed The Mulch Spider’s Dream, and then we exhibited your installation Bog Myrtle and Flamethrowers, which resulted from an Alchemy artist residency last summer in Hawick. But this title is simply Phytography. Is it a distillation, a conclusion?

What I am trying to do is to take the signals perceived from the plants as meaningful. However, it is tempting to ‘fill in’ the blanks. I have a strong imagination and upon seeing all these colours, shapes, structures and rhythms, the temptation to anthropomorphise is always present. In this film I have tried to step back as much as possible and let the plants speak for themselves. Hence the simple title.

Derek Jenkins, The Shouting Flower

This is a very teasing film. As soon as we grasp the meaning or clarity of one scene, it cuts to another, often mid-sentence. What processes are unfolding, at play?

What we’re hearing is the film’s resistance to narrative foreclosure. It is the film’s refusal to privilege my desires for what a film may be and how a film should behave. In one sense, The Shouting Flower is merely the outcome of ritualised behaviours designed to open up the work to contributions from my child and the plant itself. I gave myself certain rules and parameters, documented the performance, and the result is a film. I like to make work this way generally, but here the specific methodology was intended to hold space for my collaborators.

My efforts to impose coherence on the film with a voiceover are undermined by the peculiar way I interact with technology. In the first instance, this involved letting my child record sounds for the film on a toy cassette recorder. When she lost interest in that contribution, I picked up the toy and continued on my own, recording notes I had taken over the course of making the film. While dubbing to digital, I ‘performed’ the cassette live, moving back and forth at random through the tape until I had finally recorded most of these epigrammatic notes. This live recording, with just a few minor cuts, provides the structure of the edit. By proceeding this way, I hoped to allow the work a hand in arranging itself, to introduce chance and therefore mitigate my control, amplifying the influence of my collaborators on the shape and content of the work.

Tell us about the social or political significance of the dandelion. What can we learn from it?

I first started thinking of the dandelion as a figure for radical ideas and action when I read ‘Oppose and Propose!’ [readable here], Andrew Cornell’s brief account of the Movement for a New Society, a pacifist direct action group whose newsletter was named for the plant. Other anarchist publications had used the name before, but the MNS emphasis on tactical resistance and direct action resonates with the flower’s relationship to power. In North America, dandelions exemplify the limits of the state’s influence on wildness, and they stand against the logic that capital mobilises to determine disposability. The flower is striking and lovely, but it wilts when picked and cannot be commodified for its beauty.

As a reluctant mortgager, for me the plant signifies a resistance to a particular strain of social reproduction – the hegemonic domesticity of lawncare. I experience this pressure to tend anxiously to my home as an extension of the woeful and violent financialization of the North American real estate market. My neighbours experience the dandelion as an assault on their investments. Like many urban residents, I live in a city where rent has outpaced income for the better part of a decade, which, combined with a relatively high poverty rate, constitutes a crisis of housing insecurity. The Shouting Flower was made against the backdrop of two prolonged rent strikes and a local ‘riot’ in a gentrified neighbourhood which resulted in the arrest of several housing rights activists. A notorious local jail looms in the background of the final shot. The black balloon was given to my child at a noise protest in support of one of the activists. These dandelion-covered hills were the site of that protest. Meek as it may seem, the flower became for me a powerful symbol of resistance in this context.

Certainly, that the plant thrives in open terrain, and spread across North America along with European settlers, carries colonial implications that we must think through. It’s a rich figure for thinking about all aspects of our political lives. But I would argue that we can also learn a lot about how radical ideas might take root under capitalism from the plant’s strategies of reproduction. For years, I experienced the plant principally through my child, who knew it as the only flower she could freely pick, and, in the seed head stage, as a satisfying explosion of white fluff. Indeed, children and play represent an iconic method of dandelion dispersal. It’s a flower, and an idea, that spreads through joy.

Alchemy Film & Arts

Room 305

Heart of Hawick

Hawick

TD9 0AE

info@alchemyfilmandarts.org.uk

01450 367 352

Charity Number: SC042142

© 2024 Alchemy Film & Arts